Evolution of web development

The Evolution of a programmer joke exists for many different languages. I think there’s also room here for evolution of a web developer. I grew up making websites during the Web 1.0 era for fun, began developing professionally in the 2010s, and have been doing mostly web stuff ever since. It’s 2023 now, so I’ve been twiddling with HTML for over 20 years at this point.

Ye Olde Webb

Websites in the 1.0 era (1990s — early 2000s) were mainly static. Think digital brochures. The era when <table> reigned supreme, spacer.gif was a design pattern, and “this website is optimized for 1024x768” was not an uncommon sight. A live example I managed to find is the Heaven’s Gate website. Yes, that Heaven’s Gate (who is renewing that domain every year?!).

In some ways this was a simpler time of web development, but in many ways it was more complicated. There were so few features to make a great looking website; CSS wasn’t available until 1996, making things look right cross-browser was ridiculous (just look up Acid1 or Acid2 test results), and your connection speed was probably a crawl. But user expectations were low, and if the site just managed to work without needing to change your resolution it was a pretty good experience.

If you wanted to have fancy interactions, or animations you had to use Adobe Flash. Websites used Flash to do stuff from just animating their menu to putting their entire website into a Flash application. My biggest memory of Flash is that it meant the site was going to take all day to download over my dial-up connection. Alternatively, there was an idea called DHTML. What is DHTML? Well, it’s… HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. It’s Dynamic HTML. You want to have a dropdown navigation? You want to have bubbles follow your cursor? You want to have snowflakes falling on your webpage during Christmas time? DHTML, baby. Somehow the website Dynamic Drive has survived through the years, and I bet you can find snippets for all of those things there. The point here is: for the most part, JavaScript was an additive to the website, not the foundation.

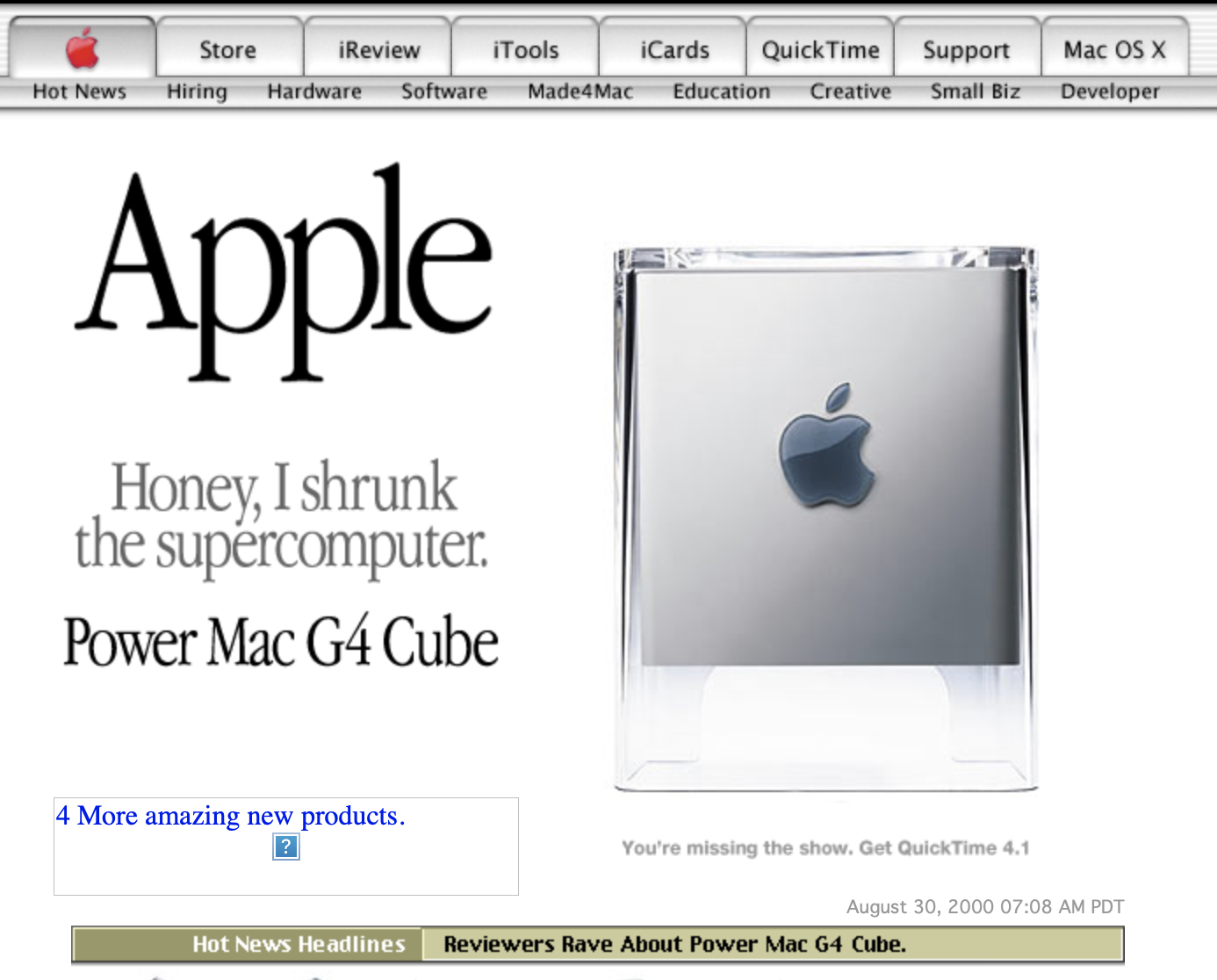

Apple homepage, c.2000 Look at the subtle off-white coloring. The tasteful thickness of it. Oh, my god. It even has a watermark.

The great thing about this era of the web was you could just view source on any website and understand how something was done. Two things I remember distinctly was the first time I saw an image map, and the first time I saw a div that was floating. Amazingly, all I had to do was view source on the page and piece together the markup and CSS, and I could do the same on my website. It was a great time to learn how to build websites hands-on. The barrier for entry was especially low, too. Fire up notepad.exe and go.

Web 1.0 sites were simple because there was low interaction, not because the HTML and CSS themselves were nascient. The paradigm for what a website is began shifting with the rise of social media websites, and other user-generated-content platforms.

Web 2.0, you are here

The dileneation between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 is the rise of websites that allow users to generate content. Myspace, Facebook, and many other websites all popped up around this time. Websites began focusing more on user experience, doing things like dynamically fetching content. “Ah, that’s just fetch” you say stupidly. No.

If you wanted to fetch content in the 1.0 days, you’d just have to do a full page refresh. Around the year 2000 you could use ActiveX to fetch content asynchronously. This later became XMLHTTPRequest. Okay, must be straightforward to write some JavaScript to do that, right? Wrong. (Just look through some of the source code of jQuery and you’ll understand why it was used everywhere.)

With increasing webpage complexity, new solutions to new problems emerged. Now your front end code might be complicated. You may be using a CSS framework to create your UI. You’ve got some complicated front end for managing state around your AJAX requests. I can’t say exactly what happened from the mid-2000s until the 2010s because I wasn’t living it. But at my first job in 2012, I remember transitioning from just HTML-over-the-wire and jQuery to single page applications.

Rise of SPAs

At my first job we’d been writing services in the .NET framework, serving HTML over the wire. The front ends were spiced up with jQuery. All was well with the world, with the exception that still there were cross-browser issues with CSS (because IE6 wasn’t deprecated). There was one seasoned developer who was very good at JavaScript, and had been toying with NodeJS on some projects. I think this was the catalyst for me stumbling across AngularJS. Wow, what in tarnation? I can write all this stuff on the front end by returning data from my APIs? Wild. Funnily enough, jQuery was so prominent that angular.element would return a jQuery element if it was available.

We tried the whole MEAN stack (Mongo, Express, Angular, Node). It felt like we could move at lightning speed compared to C#. At this point we were bundling all the third party code into one minified JS file, and all of our source code into another minified JS file. We used either Grunt or gulp as task runners to concat, minify and add source maps. The development in some ways was easier, but there are many complexities introduced with SPAs that you pay for later.

Problems with SPAs

Problems initially with SPAs:

- Big JavaScript bundles. There was no way to chunk or lazy load your assets.

- Your whole application has no types, a blessing and a curse.

- No server-side rendering, no SEO.

Initial page load times are bad because we’re downloading a significant amount of JavaScript. When SPAs first started taking over, sites would still ship a couple of big bundles for the entire application. Later, codesplitting was made possible with tools like Webpack. But while that helped mitigate large bundles, excessive splitting could still impact performance. And regardless of any splitting, you’ve still got to download and parse out the framework you’re using at page load.

JavaScript suffers the same problems every dynamically typed language does. It’s not its fault. As SPAs grow larger, understanding the code base becomes more challenging, and there’s more chance for errors when there are no types. TypeScript has basically become the defacto choice for some sort of typing in JavaScript. It’s not a free addition, though. You may hit issues with dependencies using a different version of TypeScript, you’ve got to add more tools to your build chain, etc.

Server side rendering (SSR) offered SPAs some benefits; now the pages could be indexed, and initial page load time was reduced. But it also introduces its own set of complexities. I’m out of my realm discussing this since I’ve never needed to do it, but you can google “react hydration error” and see that it’s not without its own demons.

It turns out these issues did not exist in Web 1.0. HTML was rendered on the server. There were no large JavaScript bundles to download because interactivity was low. If your backend had types, you had types. SPAs are a great choice when they’re a great choice, but there’s a lot of complexity introduced here.

Why go through all of this?

Return to simplicity

We need some way to address the pitfalls of Web 1.0 and the pitfalls of SPAs, without introducing more complexity. Until recently, it feels like we’re all going full sunken-cost on SPAs: adding tool after tool to compensate for whatever weakness SPAs have rather than asking why are we even doing this.

The complexities of SPAs come from treating your browser like any other client. It simply isn’t. It makes sense to deliver content in a way it understands. Your browser understands hypermedia. Other services calling yours understand data. It makes sense to have two different APIs for two different use cases. You wouldn’t force a microservice calling yours to parse HTML for the response it wants, so why make your browser parse JSON to render a <div>?

The outstanding issues we need to solve are: handling full-page reloads feels slow; we need a nice way to bundle our JavaScript; and we may need some highly-interactive pages depending on the product.

Libraries like HTMX, Turbo, and Unpoly are modern tools that help you write simpler websites. It doesn’t mean you can’t add JavaScript to your page; it means you get the ease of Web 1.0 and you can add complexities as you like. A common feature among all of them is the ability to transform full-page reloads into what feels like SPA transition. That’s a huge drawback to Web 1.0 already gone. You get to serve HTML over the wire for your client (the browser) and these libraries handle the swapping and merging of content into the window, and history state. And don’t think these are second-rate libraries! People are building actual web applications with these, reducing their lines of code, and delivering faster. Try it yourself and look at your Lighthouse scores. You will be surprised.

One reason for bundling all files together in the first place is because over HTTP1.1, the browser essentially punishes you for having many files to fetch. Browsers only allow a handful of connections going to your domain at once. HTTP2 solves this and makes multiple requests over a single connection, removing the drawback of serving multiple files. Additionally, modern browsers support import maps, and by extension modules. Each page of your site can still embed the scripts it needs with <script> tags, and use an import map to resolve dependencies. No more chunking and splitting. Your build steps just needs a way to generate the import map.

Everything has come a long way since 1999. HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and especially browsers. You can get really far with semantic HTML tags and modern CSS and make things look great and consistent across all modern browsers. You’ll still need some interactivity, and because the web has evolved, it’s possible without jQuery. There are libraries like AlpineJS and Stimulus that are lightweight and might be a good fit for a project in combination with serving HTML over the wire.

And, just to wrap up, a couple of hot takes.

- I don’t even think minifying is that important. Serve content gzipped. It’s probably a free feature of your server or CDN, keeps your build times low, and you don’t need to worry about sourcemaps.

- Don’t default to TypeScript. You can still get some benefits from TypeScript by using JSDoc comments and not add any additional build steps to your pipeline, if that’s an area you’re concerned about.

The punchline

Web 1.0 forms

<form action="/send-feedback" method="POST">

<dl>

<dt><label for="name">Name:</label></dt>

<dd><input type="text" name="name" id="name" /></dd>

<dt><label for="comments">Comments:</label></dt>

<dd><textarea name="comments" id="comments"></textarea></dd>

</dl>

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>Modern-day SPA forms (I think you could do much more here, but this is what ChatGPT gave me.)

import React, { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

const OvercomplicatedForm = () => {

const [formData, setFormData] = useState({ name: '', comments: '' });

const [isSubmitting, setIsSubmitting] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

const submitForm = async () => {

if (isSubmitting) {

try {

const response = await fetch('/send-feedback', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

},

body: JSON.stringify(formData),

});

if (response.ok) {

console.log('Form submitted successfully!');

} else {

console.error('Error submitting form');

}

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error submitting form', error);

} finally {

setIsSubmitting(false);

}

}

};

submitForm();

}, [formData, isSubmitting]);

const handleChange = (e) => {

setFormData({ ...formData, [e.target.name]: e.target.value });

};

const handleSubmit = (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

setIsSubmitting(true);

};

return (

<div>

<form onSubmit={handleSubmit}>

<label>

Name:

<input

type="text"

name="name"

value={formData.name}

onChange={handleChange}

/>

</label>

<br />

<label>

Comments:

<textarea

name="comments"

value={formData.comments}

onChange={handleChange}

></textarea>

</label>

<br />

<button type="submit" disabled={isSubmitting}>

{isSubmitting ? 'Submitting...' : 'Submit'}

</button>

</form>

</div>

);

};

export default OvercomplicatedForm;RETVRN TO NATVRE

<form action="/send-feedback" method="POST">

<dl>

<dt><label for="name">Name:</label></dt>

<dd><input type="text" name="name" id="name" /></dd>

<dt><label for="comments">Comments:</label></dt>

<dd><textarea name="comments" id="comments"></textarea></dd>

</dl>

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

</form>